RARE Autograph Letter Signed- 1809 David L Barnes vs West 1st Supreme Court Case

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

RARE Autograph Letter Signed- 1809 David L Barnes vs West 1st Supreme Court Case:

$2450.00

RARE Autograph Letter Signed

Signedby

David Leonard Barnes

Barnes vs. West - Won FIRST Supreme Court Decision(see below)

1809

For offer, an early ORIGINAL American letter. Fresh from an estate collection. Never offered on the market until now.Vintage, Old, antique, Original - NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed !!I could not locate any other examples for sale. I only found examples in the Library of Congress to Thomas Jefferson.

David Leonard Barnes,(January 28, 1760 – November 3, 1812) was a United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Rhode Island and a party and attorney in the first United States Supreme Court decision, West v. Barnes (1791). He won the case.Education and career

Born on January 28, 1760, in Scituate, Province of Massachusetts Bay, British America, Barnes graduated from Harvard University in 1780 and read law in 1783. He entered private practice in Taunton, Massachusetts from 1783 to 1793. He continued private practice in Providence, Rhode Island from 1793 to 1802.[1] He was United States Attorney for the District of Rhode Island from 1797 to 1801.[2]

West v. Barnes

Barnes won the case of West v. Barnes (1791) representing himself and his wife\'s family after being admitted to the Supreme Court bar that morning.[3]

Federal judicial service

Barnes received a recess appointment from President Thomas Jefferson on April 30, 1801, to a seat on the United States District Court for the District of Rhode Island vacated by Judge Benjamin Bourne. He was nominated to the same position by President Jefferson on January 6, 1802. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on January 26, 1802, and received his commission the same day. His service terminated on November 3, 1812, due to his death in Providence.[1] He was interred at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence.[4]

Family

Barnes married into the Jenckes family of Providence.

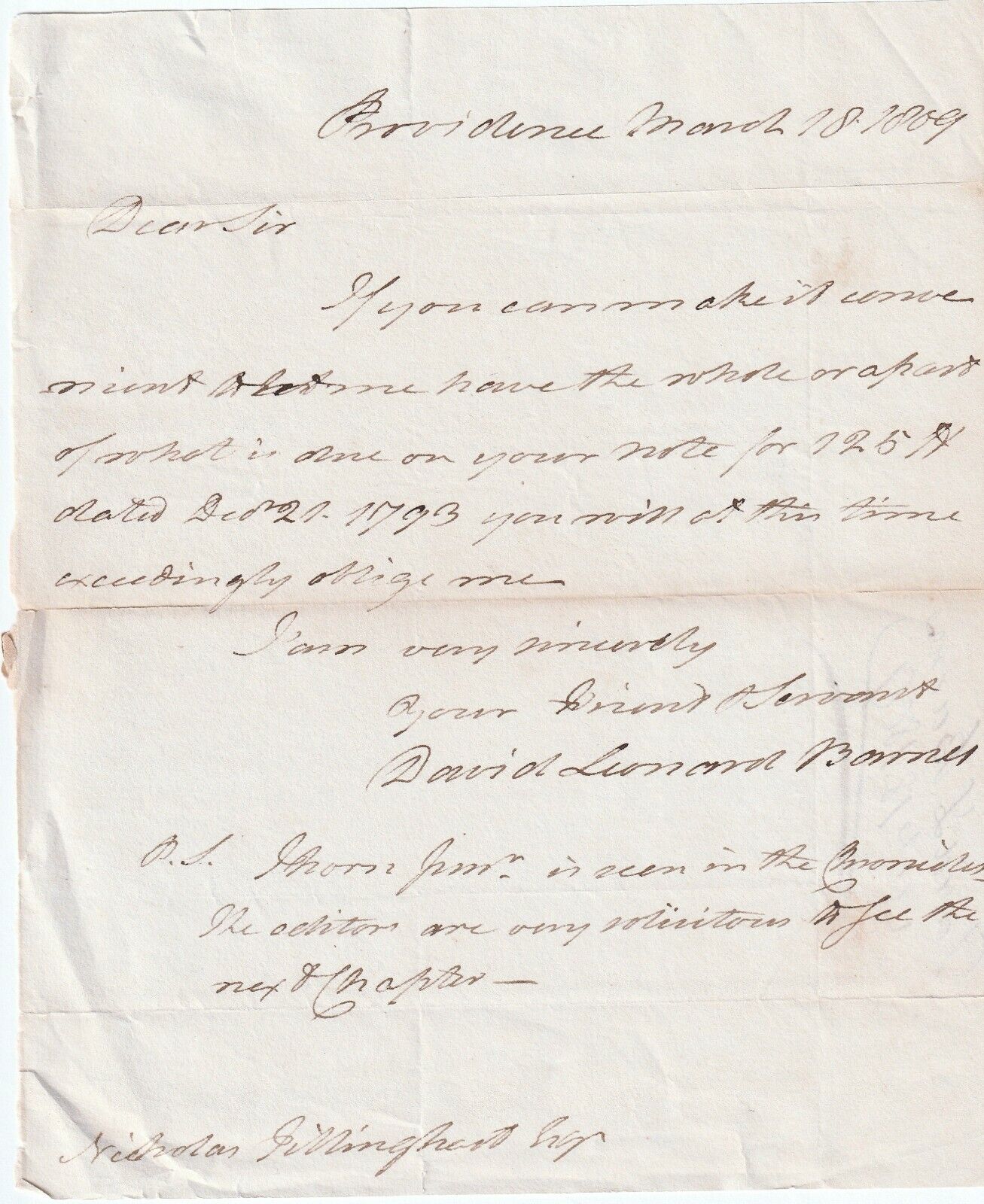

Letter to Nicholas Fillinhart / Fillingdard ? - can\'t make out recipient. Dated March 18, 1809, Providence. Signed \"your friend & servant\". One page ALS. Writing on back. In good to very good condition. Fold marks, starting to separate at edges. NOTE: Will be send folded, as found, and shown in last photo.Please see photos for details. If you collect Americana history, American politics, Colonial America, manuscript, etc., this is one you will not see again. A nice piece for your paper / ephemera collection. Perhaps some genealogy research information as well. Combine shipping on multiple offer wins! 2648

Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Rhode IslandIn officeApril 30, 1801 – November 3, 1812Appointed by Thomas JeffersonPreceded by Benjamin BourneSucceeded by David HowellPersonal detailsBorn David Leonard BarnesJanuary 28, 1760Scituate,Province of Massachusetts Bay,British AmericaDied November 3, 1812 (aged 52)Providence, Rhode IslandResting place Swan Point CemeteryProvidence, Rhode IslandEducation Harvard Universityread law

West v. Barnes, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 401 (1791), was the first United States Supreme Court decision and the earliest case calling for oral argument.[1][2] Van Staphorst v. Maryland (1791) was docketed prior to West v. Barnes but settled before the Court heard the case: West was argued on August 2 and decided on August 3, 1791. Collet v. Collet (1792) was the first appellate case docketed with the Court but was dropped before it could be heard.[3] Supreme Court Reporter Alexander Dallas did not publish the justices\' full opinions in West v. Barnes, which were published in various newspapers around the country at the time, but he published an abbreviated summary of the decision.

The Court ultimately decided the case on procedural grounds, holding that a writ of error (an appeal) must be issued within ten days by the Clerk of the Supreme Court of the United States as required by federal statute, and not by a lower court located closer to the plaintiff in Rhode Island. As a result of this case, Congress ultimately changed this procedure with the ninth section of the Process and Compensation Act of 1792, allowing circuit courts to issue these writs, thereby assisting citizens living far away from the capital.[4]

BackgroundThis was one of the earliest potential cases of judicial review in the United States where the Court had the opportunity to overturn a Rhode Island state statute regarding lodging payment of a debt in paper currency in fulfillment of a contract. The court did not exercise judicial review in deference to the legislature. The court ultimately decided against William West, the petitioner, on procedural grounds.[3][5]

William West was a farmer, anti-federalist leader, revolutionary war general, and judge from Scituate, Rhode Island. He owed a mortgage on his farm from a failed molasses deal in 1763 to the Jenckes family from Providence. He made payments on the mortgage for twenty years, and in 1785 asked the state for permission to conduct a lottery to help pay off the remainder. Due to his service during the Revolution, the state granted him permission. Much of the proceeds were paid in paper currency instead of gold or silver. West tendered payment in the paper currency as allowed by state statute, \"lodging\" the funds with a state judge to be collected within ten days.[4]

David L. Barnes, a Jenckes heir, and well-known attorney and later federal judge, brought suit in federal court based on diversity jurisdiction asserting that gold or silver payment was required, and refusing the paper currency. Despite lack of formal training, West represented himself pro se in the circuit court in June 1791 before Chief Justice John Jay, Associate Justice William Cushing, and Henry Marchant. They rejected his arguments. West then pursued appeal to the Supreme Court on a writ of error, attempting to comply with all statutory directions. West was unable to make the journey to Philadelphia to represent himself, so he engaged William Bradford, Jr., Pennsylvania\'s attorney general, to represent him. On appeal, Barnes focused on the procedural irregularities. Barnes asserted that the writ had been signed and sealed only by the clerk of the circuit court in Rhode Island instead of by the Supreme Court clerk, which he claimed as necessary. This was asserted despite the fact that West would have had to make an arduous journey in 1791 to Philadelphia within ten days to do so. West lost on this procedural issue and was eventually forced to relinquish his farm.[4]

OpinionsThe court\'s opinion was extensively covered by period newspapers as no official court reporter was yet published in 1791, and the seriatim opinions were republished in the newspapers and are currently accessible in James R. Perry\'s The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800, Volume 6, \"West v. Barnes,\" pp. 3-27. [5]. Each of the five justices issued a seriatim opinion regarding the writ of error, and the justices unsuccessfully looked to common law precedent from state courts and pre-Revolution English case law including Coke and Blackstone\'s treatises. Several of the justices expressed their reservations about the federal statute and suggested alternatives for filing within the ten-day statutory period, but nevertheless each justice refused to expand the meaning of the statute believing that only Congress had the power to do so.[4] In summation the Dallas reporter quoted John Jay and summed up the case holding as follows:

West, Plaintiff in error, v. Barnes et al.

On the first day of the term, Bradford presented to the court, a writ, purporting to be a writ of error, issued out of the office of the clerk of the circuit court for Rhode Island district, directed to that court, and commanding a return of the judgment and proceedings rendered by them in this cause: And thereupon he moved for a rule, that the defendant rejoin to the errors assigned in this cause.

Barnes, one of the defendants, (a counsellor of the court) objected to the validity of the writ, that it had issued out of the wrong office: and, after argument,

THE COURT were unanimously of opinion, That writs of error to remove causes to this court from inferior courts, can regularly issue only from the clerk\'s office of the court.

Motion refused.[6]

AftermathJustice James Iredell was upset by the governing statute and wrote to President Washington to change the law, which allowed only the clerk of the Supreme Court to issue writs of error. The Process and Compensation Act of 1792 altered the law to prevent such hardships for future litigants.[7]

Several months after the decision, on November 9, 1791, Barnes brought another suit of ejectment to eject West from the mortgaged farm. He filed suit in the Circuit Court for the District of Rhode Island. Justice Jay, Justice Cushing and Judge Henry Marchant held the plea bad for a second time. They decided that William West lodged payment of his debt with a Rhode Island judge on September 16, and so Barnes had ten days to collect it, according to the state statute. The Rhode Island \"lodging\" Act was, however, suspended on the 19th of that month and so the ten-day period could not fully occur since only three days had passed and was thus not conformable to the statute. Barnes eventually won the ejectment case, but he had difficulty ejecting West\'s family from the farm, as West had sold the farm to a son-in-law. West\'s estate continued to be disputed after his death, resulting in the First Circuit decision West v. Randall in 1820.

According to Cotter v. Alabama, \"Prior to 1791 it was the practice that a writ of error could only issue from the office of the clerk of the supreme court. In Mussina v. Cavazos, ([73, US 355], 6 Wall. 355), it is stated that a decision to that effect in West v. Barnes... led to the enactment of the ninth section of the act of 1792, being section 1004 of the Revised Statutes...\" (Cotter v. Alabama G. S. R. Co., 61 F. 747, 748 (6th Cir. 1894)).

See also Wikisource has original text related to this article:West v. BarnesList of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 2List of United States Supreme Court cases prior to the Marshall CourtWilliam West

In the United States, the title of federal judge means a judge (pursuant to Article Three of the United States Constitution) nominated by the president of the United States and confirmed by the United States Senate pursuant to the Appointments Clause in Article II of the United States Constitution.

In addition to the Supreme Court of the United States, whose existence and some aspects of whose jurisdiction are beyond the constitutional power of Congress to alter, Congress has established 13 courts of appeals (also called \"circuit courts\") with appellate jurisdiction over different regions of the United States, and 94 United States district courts.

Every judge appointed to such a court may be categorized as a federal judge; such positions include the chief justice and associate justices of the Supreme Court, circuit judges of the courts of appeals, and district judges of the United States district courts. All of these judges described thus far are referred to sometimes as \"Article III judges\" because they exercise the judicial power vested in the judicial branch of the federal government by Article III of the U.S. Constitution. In addition, judges of the Court of International Trade exercise judicial power pursuant to Article III.

Other judges serving in the federal courts, including magistrate judges and bankruptcy judges, are also sometimes referred to as \"federal judges\"; however, they are neither appointed by the president nor confirmed by the Senate, and their power derives from Article I instead.The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States of America. It has ultimate and largely discretionary appellate jurisdiction over all federal and state court cases that involve a point of federal law, and original jurisdiction over a narrow range of cases, specifically \"all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party.\"[2] The Court holds the power of judicial review, the ability to invalidate a statute for violating a provision of the Constitution. It is also able to strike down presidential directives for violating either the Constitution or statutory law.[3] However, it may act only within the context of a case in an area of law over which it has jurisdiction. The Court may decide cases having political overtones but has ruled that it does not have power to decide non-justiciable political questions.

Established by Article Three of the United States Constitution, the composition and procedures of the Supreme Court were initially established by the 1st Congress through the Judiciary Act of 1789. As later set by the Judiciary Act of 1869, the Court consists of the chief justice of the United States and eight associate justices. Each justice has lifetime tenure, meaning they remain on the Court until they resign, retire, die, or are removed from office.[4] When a vacancy occurs, the president, with the advice and consent of the Senate, appoints a new justice. Each justice has a single vote in deciding the cases argued before the Court. When in majority, the chief justice decides who writes the opinion of the court; otherwise, the most senior justice in the majority assigns the task of writing the opinion.

The Court meets in the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. Its law enforcement arm is the Supreme Court Police.

RARE Autograph Letter Signed- 1809 David L Barnes vs West 1st Supreme Court Case:

$2450.00